UH Rainbow Part of Important New Clinical Trial of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Young Children

February 03, 2021

Benefits shown for both children and parents

Innovations in Pediatrics | Winter 2021

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), a small wearable device that provides an interstitial glucose value every five minutes, can be an effective tool for even very young children with type 1 diabetes and is even more helpful to parents when introduced with a short but structured education program. Those are the conclusions of a new multicenter, randomized controlled trial, which included 143 youth with type 1 diabetes between the ages of 2 and 8 years, followed over six months.

Jamie Wood, MD

Jamie Wood, MDThis is among the first studies to show a benefit of CGM for this young age group, says Jamie Wood, MD, Medical Director of Pediatric Diabetes, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at UH Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital and co-investigator and co-author of the new study. The study was published recently in the journal Diabetes Care. Dr. Wood is also Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

“At the time we began this study, there were no data demonstrating improved glycemic control with CGM use in young children and no randomized controlled trials of CGM compared with blood glucose monitoring of six months duration in very young children,” Dr. Wood says.

The study results, she says, also highlight the importance of parent education.

“Despite families’ access to CGM technology, oftentimes we will not see a difference in A1C,” she says. “With this study, our hope was that by offering them the technology and teaching families how to use it, they would be more successful.”

For the study, dubbed Strategies to Enhance New CGM Use in Early Childhood (SENCE), researchers at 14 pediatric endocrinology practices across the U.S. randomly assigned participants to one of three diabetes monitoring strategies over 26 weeks: CGM with standardized training and a family behavioral intervention, CGM with standardized training or fingerstick blood glucose monitoring without CGM. All study groups had scheduled in-clinic visits at 6, 13, 19 and 26 weeks and phone calls at 10, 16, and 22 weeks following randomization. Caregivers of participants in the family behavioral intervention group also participated in standardized ~ 30 minute interactive training sessions at the 1, 3, 6, 13 and 19 week visits delivered by a research assistant trained by the study team.

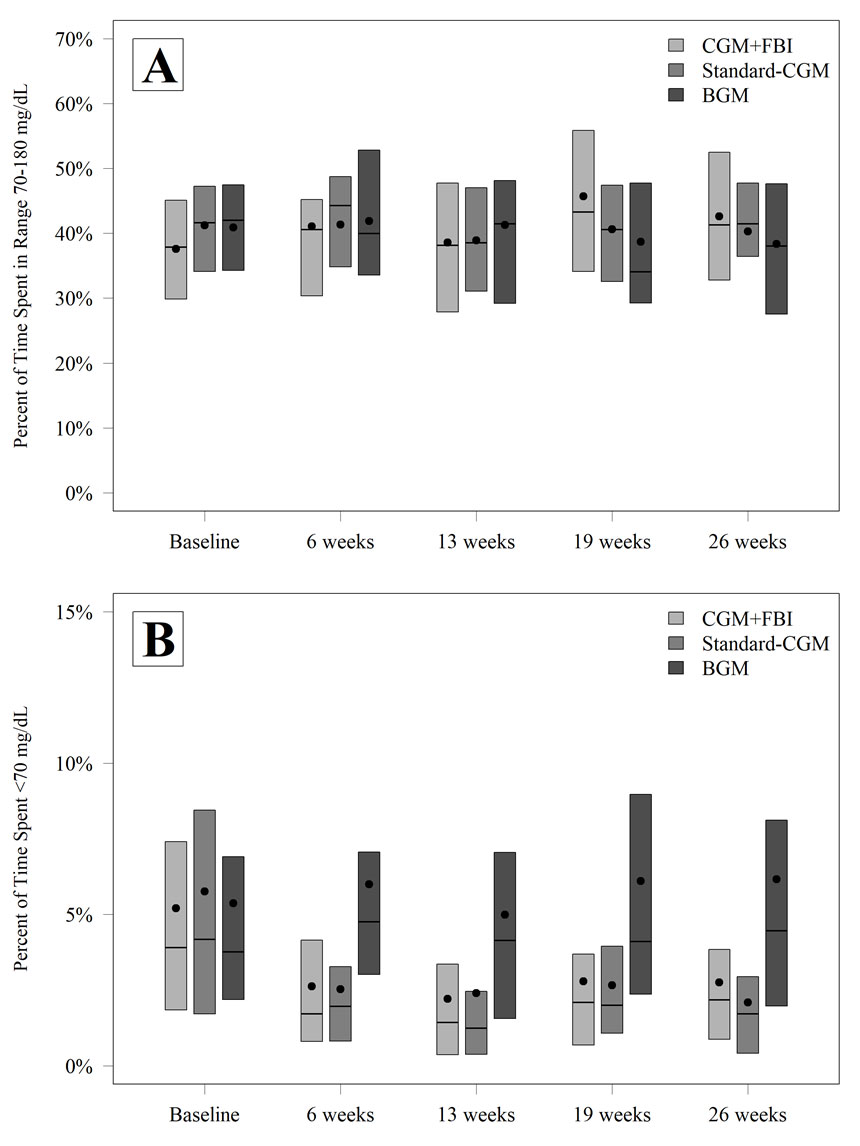

Figure 1—TIR 70–180 mg/dL (A) and time with glucose level ,70 mg/dL (B) by treatment group and visit.

Figure 1—TIR 70–180 mg/dL (A) and time with glucose level ,70 mg/dL (B) by treatment group and visit.“Psychologists, social workers, and physicians on the study team designed the family behavioral intervention content to address family feelings, attitudes and behaviors that can be barriers to CGM use, and to teach skills to manage behavioral barriers to CGM use,” says Sarah MacLeish, DO, Principal Investigator and Associate Medical Director of Pediatric Diabetes at UH Rainbow. Dr. MacLeish is also Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the School of Medicine.

Sarah MacLeish, DO

Sarah MacLeish, DO“We had one of our diabetes research nurses teach them the technology and provide parents the tools to help their child adapt to the technology to be successful with it,” adds Dr. Wood.

At each visit, the study team used information from the CGM downloads to make insulin dose adjustments and other suggestions for improvement. This information included the percent of time spent in target range of 70-180 mg/dL, mean glucose, glucose variability, time in hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic ranges, rate of hypoglycemic events per week, and A1C at 26 weeks.

Results show that while study participants using a CGM device did not improve their glucose “time in range” over the six-month period, they did reduce their time in hypoglycemia. In addition, the family behavioral intervention was shown to benefit parental well-being, as reported on a series of different questionnaires.

“The hypoglycemia improved a lot,” Dr. MacLeish says. “That was one of the biggest positive findings. No severe hypoglycemia events occurred in the CGM group with the family behavioral intervention, while one occurred in the standard CGM group, and five occurred in the blood glucose monitoring control group. That is a pretty great outcome. Plus, the actual percent of time in hypoglycemia shown on the continuous glucose monitor was much better. In addition, there was a decrease in time over 300 mg/dL, although no change in total time over 180 mg/dL.

Wendy Campbell, RN, displays continuous glucose monitor device.

Wendy Campbell, RN, displays continuous glucose monitor device.As encouraging as these results are for the use of CGM devices in young children with diabetes, Dr. Wood and Dr. MacLeish say, they’re almost equally important in showing the benefits for the mental health of parents.

“Having a child with diabetes is extremely stressful, but this relatively simple intervention can help relieve that stress,” Dr. MacLeish says.

Simplicity, they say, is key.

“The family behavioral intervention was designed so that it doesn't have to be given by a nurse or a doctor, it can just be given by a person who's trained to do it,” Dr. Wood says. “We did that on purpose so that it could be widely used.”