DCCT-EDIC at 40: University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital Plays Pivotal Role in Landmark Type 1 Diabetes Study

February 26, 2023

UH Rainbow has served as clinical coordinating center for the study for decades, providing research oversight of 27 sites in the U.S. and Canada

Innovations in Pediatrics | Winter 2023

Forty years ago, endocrinologists across the U.S. and Canada posed a key question: Could intensive management of type 1 diabetes – defined as multiple injections of insulin each day – be a better alternative to standard management and help patients achieve near-normal blood glucose levels – lessening the long-term complications of the disease?

Unacceptably high rates of type 1 diabetes complications motivated the search for better treatment approaches. So in 1983, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) trial to study the “glucose hypothesis” in adolescent and young adult patients with type 1 diabetes. UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital joined the study as co-chair, enrolling the nation’s youngest patient – then age 13. That patient is still enrolled in the study today at UH Rainbow.

Rose Gubitosi-Klug, MD

Rose Gubitosi-Klug, MD“This study was needed to help us with the public health crisis of how to manage type 1 diabetes better,” says Rose Gubitosi-Klug, MD, PhD, Division Chief of Pediatric Endocrinology at UH Rainbow and William T. Dahms Chair in Pediatric Endocrinology.

The early findings were groundbreaking.

“The DCCT showed that people with type 1 diabetes who kept their blood glucose levels as close to normal as safely possible with intensive diabetes treatment as early as possible in their disease had fewer diabetes-related health problems after 6.5 years, compared with people who used the conventional treatment,” Dr. Gubitosi-Klug says. “DCCT showed that people who used intensive treatment lowered their risk of eye, kidney and nerve complications.”

Diabetes Technology Evolves, Thanks in Part to DCCT/EDIC

The benefits of intensive diabetes management revealed in the DCCT trial helped set the stage for technologic advancements in diabetes management that would flow from the EDIC trial, allowing more frequent glucose testing and insulin dosing to reduce patient burden.

Consider the change these two trials have effected:

DCCT: 1983 – 1993 | Before technology

- Glucose monitoring via urine

- Administration of insulin (less physiologic kinetics, fewer insulin types available)

- Prescribing diets using ADA exchange lists co-managed with insulin dose

EDIC: 1993 – Present | After technology

- Glucose meters - Early glucose meters were larger and still required multiple daily finger sticks.

- Continuous glucose monitors (CGM) - Evolved from requiring patient calibration to now coming factory-calibrated and FDA-approval to use sensor glucose readings for insulin dosing.

- Insulin pumps - Progressed from large devices to small, personal wearable devices that delivered insulin only, to the most recent versions that communicate with CGM, independent of user, to manage between meal glucose excursions.

- Insulin - Insulin now matched to grams of food that is actually eaten - carbohydrate-counting by grams and not exchanges, and inclusion of dietary counseling has propelled self-management of diabetes.

Leadership Role for UH Rainbow

The DCCT evolved into the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study, the long-term follow-up to DCCT cohort of participants, in 1993, with the goal of understanding how diabetes affects the body over time and the long-term benefits of a period of early and intensive blood glucose control in the development of later diabetes complications. Dr. Gubitosi-Klug joined the DCCT/EDIC study in 2007, and has served as principal investigator in UH Rainbow’s role as the national clinical coordinating center for the past 15 years. The work is demanding, but it’s a role she relishes, she says.

“This is a very large study with many sites,” she says. “As a result, we built a system that brought central oversight of the regulatory, financial and institution review board materials, making sure that each institution and their coordinator and investigator had all of the materials and equipment to perform the study. There’s always variation in institutions and what support they need. But the goal was to make sure that every participant who has been enrolled, stayed enrolled, and continues to follow up with the study over time. That's what the real power of the EDIC study is.”

This approach is working: As DCCT/EDIC enters into its 41st year, its researchers continue to follow about 90 percent of the surviving cohort. For her part, Dr. Gubitosi-Klug continues to follow about 40 type 1 diabetes study participants at her site.

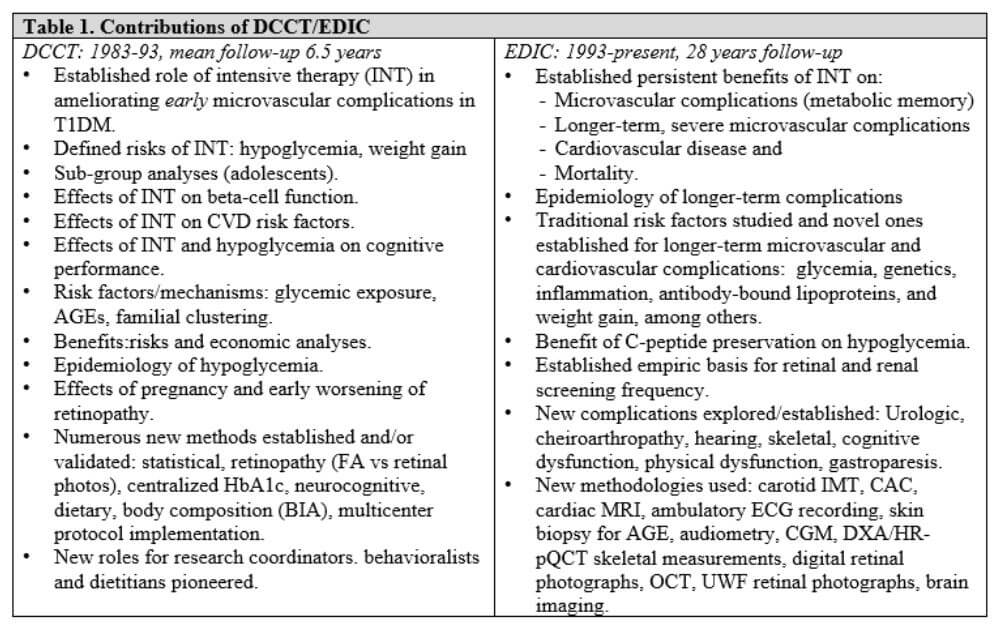

Forty Years of Findings

Dr. Gubitosi-Klug says it’s impossible to overstate the difference the EDIC study has made in treating patients with type 1 diabetes.

“It changed everything from day one,” she says. “When I meet a new child with type 1 diabetes and the family is anxious, I tell them because of this study, if you can keep your A1C value 7 or below, you will have a very limited chance of any eye disease and you'll reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease by over 50 percent. In terms of life expectancy, we've demonstrated that if you manage your diabetes well, you can live similar to the average life expectancy of adults without diabetes in America today.”

EDIC has shown that early and intensive blood glucose control during the DCCT lowers the risk of:

- Advanced diabetic eye disease by 49 percent, 18 years after the DCCT ended and eye surgery by 49 percent, 21 years after the DCCT ended

- Advanced kidney disease by 33 percent, 24 years after the DCCT ended

- Nerve problems by about 30 percent, 14 years after the DCCT ended

- Cardiovascular diseases (such as heart attack and stroke) by 30 percent, 22 years after the DCCT ended

EDIC results have also revealed that intensive management of type 1 diabetes doesn’t have to be perfectly executed by the patient in order to achieve results, Dr. Gubitosi-Klug says.

“Our recent analysis demonstrates that improvement in management over time continues to have long-lasting effects decades later,” she says. “We can not only prevent the onset of complications, we can also make an impact in secondary prevention, slowing the progression. So if for the first 20 years of your type 1 diabetes diagnosis, you struggle, if you improve, then 30 and 40 years out, it still gives you benefit. This provides a hopeful and encouraging message to our children and youth living with type 1 diabetes, that it's really never too late to seek help in reaching and achieving their diabetes goals.”

New Frontiers for EDIC

Watch now: Rose Gubitosi-Klug, MD, PhD, chief of pediatric endocrinology & diabetes at UH Rainbow and EDIC’s current principal investigator, joins three trial participants to share what was learned from the trial and how it has transformed the management of type 1 diabetes for patients around the world.

Next, Dr. Gubitosi-Klug and colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital and other EDIC sites will undertake a new study of type 1 diabetes – the largest assessment of cardiopulmonary fitness in this population ever conducted. The researchers are adopting the Framingham protocol, comparing the 30-minute exercise bike performance of patients with type 1 diabetes to individuals of a similar age without the condition.

“If you manage your diabetes well, the structure of the heart looks good on echocardiogram and cardiac MRI, but we've never done complex measurements of how people function,” she says. “This will also be one of our first assessments of pulmonary function in patients with long-term type 1. We hypothesize that like our other long-term outcomes, that intensive management of type 1 diabetes will allow individuals to have fitness levels similar to the general population over time – that they'll age similarly.”

In addition, Dr. Gubitosi-Klug and other EDIC researchers are conducting novel investigations into the effects of long-term type 1 diabetes on brain structure. Just last year, the DCCT-EDIC Research Group reported in the journal Diabetes Care that middle-aged and older adults with type 1 showed brain volume loss and increased vascular injury when compared with control subjects without diabetes, equivalent to four to nine years of brain aging.

“Actual structural changes may relate to your history of glycemic control, so this is certainly a field of emerging interest in diabetes research,” Dr. Gubitosi-Klug says.

Research is also under way at UH Rainbow led by Dr. Gubitosi-Klug into how weight gain over time among people with type 1 diabetes may lead to insulin resistance and complicate the course of the disease.

“One thing that EDIC participants do that’s very similar to the general population is gain weight over time,” she says. “As they gain weight, they can develop insulin resistance. When the body becomes resistant, it increases the need for more insulin, which can then lead to additional weight gain. And more weight gain leads to needing more insulin, and so you get into a loop, a bit of a vicious cycle.”

Dr. Gubitosi-Klug says research will show whether it’s possible to identify and short-circuit this process earlier in the progression of type 1 disease by measuring changes in the liver.

“We can hopefully detect early signs of liver fat using Fibroscan that might signal some insulin-resistance state in our patients with type 1,” she says. “The goal is to identify the factors associated with development of liver fat and how we can prevent these diabetes-related complications in future generations.”

The NIH just renewed EDIC for five more years of funding, so more groundbreaking research into the management and effects of type 1 diabetes is sure to continue. Dr. Gubitosi-Klug says she looks forward to participating in such a consequential study for type 1 patients and their families for years to come. The best ideas for new research, she says, may come from these patients and their families themselves.

“There's always more to know,” she says. “One question leads to more questions. When it comes to research, I think the most compelling questions still come from conversations with patients, research participants and their families. We want to keep this focus on understanding the mechanisms and preventing complications of type 1 diabetes for millions of Americans living with the disease.”

Contributing Expert:

Rose Gubitosi-Klug, MD, PhD

Division Chief of Pediatric Endocrinology and William T. Dahms Chair in Pediatric Endocrinology

UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital

Professor of Pediatrics

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine