Reducing Morbidity in Testicular Cancer Treatment

April 18, 2022

Innovations in Urology | Summer 2022

Testicular cancer is the most common form of cancer in men between 18 and 44, accounting for approximately 9,000 cases annually in the U.S. Since the 1970s, when testicular cancer was essentially incurable, advances in imaging and treatment modalities, such as CT imaging and multi-agent chemotherapy, have dramatically improved this dismal statistic – improving long-term survival rates from about 5 percent to 90 percent.

Adam Calaway, MD, MPH

Adam Calaway, MD, MPHNow, says Adam Calaway, MD, MPH, a Urologic Oncologist at University Hospitals Urology Institute and Co-director of Robotic Surgery at UH Cleveland Medical Center, testicular cancer has become one of the most curable malignancies. The current challenge is to reduce treatment-related morbidity without sacrificing the increased cure rates.

Reducing the toxic burden of treatment

“Reducing morbidity is extremely important in this population, as these young men now have a long life expectancy,” says Dr. Calaway. “We’ve studied these men over the last four decades to understand that there is an expense for these high cure rates as treatment-related morbidity increases over time. We must now focus on ways to either make the treatments more tolerable, less toxic or minimize treatments needed for cure.”

In a recently published study, Dr. Calaway and a skilled team investigated outcomes in men with clinical stage II non-seminomatous germ cell tumors. Stage II tumors have evidence on imaging of enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Traditionally, these men are treated with chemotherapy, surgery or potentially both. An overarching goal of this study was to investigate ways to cure every man with only one potential treatment option.

In men with Clinical Stage II non-seminomatous germ cell tumors who undergo induction chemotherapy, there is controversy within the urology community around what to do after chemotherapy – especially in situations where there is no residual disease > 1 cm. There is a consensus, however, that in men with > 1 cm residual disease on imaging, a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection should be completed to treat the roughly 40 percent of masses that are teratoma – which is refractory to chemotherapy – and the 10 to 15 percent of masses that are active tumors.

This high-risk surgery should only be done in expert hands in select cancer centers, says Dr. Calaway, who has special training in this procedure.

“The remaining 40 to 45 percent of patients just have necrosis – not a teratoma, not active cancer,” he says. “Yet, we need to perform the dissection because we can’t tell what’s what. We operate on a lot of patients who only have post-chemotherapy scar tissue, putting them through a potentially damaging surgery with no tangible benefit, when they could instead undergo active surveillance.”

Developing predictive tools

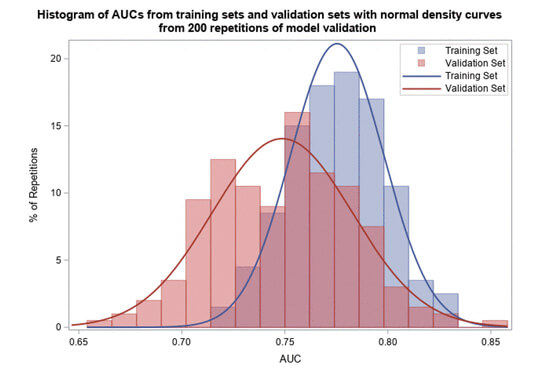

Dr. Calaway created a tool to help predict the likelihood a patient has a teratoma that requires additional surgery after chemotherapy, knowing that the amount of teratoma in the primary tumor helps predict the amount of teratoma in the retroperitoneum. Other known risk factors for teratoma, such as presence of other histologies in the orchiectomy (yolk sac tumor), tumor size and serum tumor marker elevation, were used to create this predictive tool. The group found that increasing percentages of teratoma in the orchiectomy made teratoma in the retroperitoneum even more likely. The group also found some factors which made the presence of teratoma less likely, and conversely the presence of necrosis/scar more likely.

“We wanted to see if we could really hone down and predict what’s in the abdomen and minimize surgery in patients who are not likely to benefit, those with necrosis,” he says. “It’s important to work through this in a thoughtful way. There is so much nuance.”

Dr. Calaway’s study was published in The Journal of Urology and one of the study’s images was selected to appear on the cover of the issue, a significant achievement for study authors, notes Dr. Callaway.

“Testicular cancer is curable for the most part,” says Dr. Calaway. “Although we have a variety of treatments, most have some degree of toxicity. So, our overarching goal is to maximize cure while minimizing morbidity. Perhaps by using this clinical tool and biomarkers such as microRNA 371, a biomarker for active cancer, we may be able to further reduce the treatment burden on testicular cancer patients after platinum-based chemotherapy. This could be a way forward.”

For more information about this study or testicular cancer treatment, contact Dr. Calaway, University Hospitals Urology Institute at 216-844-3009.

Adam Calaway, MD, MPHContributing Expert:

University Hospitals Urology Institute

Assistant Professor

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine