Hartwell Award Funds UH Research on Congenital Deafness

December 31, 2017

Dr. Martin Basch explores regenerative capacity of the Stria Vascularis, which may provide new therapies to treat hearing loss

UH Ear, Nose & Throat Institute - Winter 2018

Martin Basch, PhD

Martin Basch, PhD Kumar Alagramam, PhD

Kumar Alagramam, PhDThe epithelial tissue of the cochlea, the Stria Vascularis, is a new frontier in the quest to restore hearing. It is one that is being pursued with passion by Martin Basch, PhD, Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

Although 30 to 40 percent of congenital hearing loss is attributable to defects in the stria, Dr. Basch notes that the regenerative potential of this tissue has been largely unexplored.

“The root problem is that the specialized cells in the stria do not fully differentiate during embryonic development, yet they retain many characteristics of their progenitor cells and have the ability to differentiate into functionally mature intermediate cells,” he says.

In 2016, Dr. Basch received the prestigious Hartwell Individual Biomedical Research Award and a Hartwell Fellowship for his innovative biomedical research into stria. Now – funded by a three-year, $300,000 grant from The Hartwell Foundation and the $100,000 fellowship – he and his team at the School of Medicine’s Basch Lab can gain a clearer understanding of this tissue and its role as the “battery” for auditory hair cells.

STUDYING STRIA’S POTENTIAL

The research being done at the Basch Lab is significant for the School of Medicine and University Hospitals, says Kumar Alagramam, PhD, The Anthony Maniglia Chair for Research and Education, Associate Professor and Director of Research, Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery at the School of Medicine.

“It puts our research program and the UH Ear, Nose & Throat Institute on the map among peers and other research organizations,” Dr. Alagramam says. “The Basch Lab is breaking ground for the application of innovative stem cell therapies for deafness. If successful, this novel approach could provide physicians with another therapeutic option to offer patients.”

Trained as a developmental biologist, Dr. Basch’s interest in stria deepened through his postdoctoral research on neural crest tissue and the inner ear in mouse models.

“I was working, like many in my field, on hair cells,” he explains. “I realized that the neural crest cells and the Stria Vascularis are not only related, but they have potential for plasticity regeneration.”

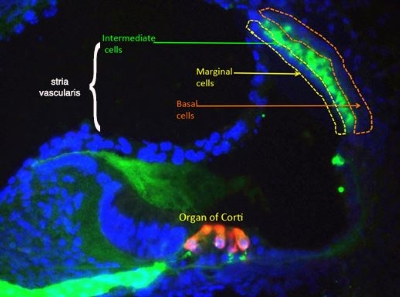

A cross section through the inner ear. Intermediate cells of the stria vascularis are shown in green. Photo credit: Martin Basch Lab

A cross section through the inner ear. Intermediate cells of the stria vascularis are shown in green. Photo credit: Martin Basch LabTo understand how the embryonic cells that pilot their way to the stria take on their specialized roles, the Basch Lab team is focused on differentiating three cell types: marginal cells, specialized melanocyte-like cells and basal cells. By engineering the cells with a fluorescent protein, they can observe what happens when the cells are implanted into mouse stria. Along with the fluorescent labeling and microscopy, the team is using endo-cochlear potential measurement (EP) and auditory brainstem response (ABR) technology to determine whether the cells are functioning as normal stria cells.

“Because the stria is located in the lateral wall of the cochlea, you do not have to puncture that organ to implant the cells as you do with hair cell repair,” Dr. Basch says. “You can just put the cells on the side. Also, we have an implantation device that has a modified pump to inject cells into the stria at very low pressure.”

NEW CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Based on the outcome of the investigations with mice, which the Hartwell grant is funding, Dr. Basch hopes to translate the methodology into clinical trials. Ultimately, he wants to work with surgeons at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital focusing on infants with syndromic congenital deafness, such as cases of Waardenburg syndrome, Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, Bartter syndrome and SeSAME syndrome.

“One of the advantages of the Stria Vascularis is that its cells come from the same progenitor population that travels to different parts of the body, such as every pigmented cell in your skin,” Dr. Basch says. “So, it is very possible that we can take a little patch of skin cells from a patient, differentiate them in a petri dish and inject those cells into the ear.

“At the time that surgeons would do a cochlear implant, we would inject these cells to see if they potentiate the effect of the cochlear implant, or if they can restore hearing without the implant.”

First the team must develop the protocol and then the human cell lines, he says.

“These babies have a very challenging life ahead of them and, if this project works, we will at least be able to palliate one of the symptoms: deafness,” Dr. Basch says.

For more information about the Basch Lab, please visit baschlab.org or contact Dr. Martin Basch at mlb202@case.edu or 216-844-2323. To learn more about The Hartwell Foundation, visit thehartwellfoundation.org.