COVID-19 Nursing Study

Throughout the pandemic, nurses mobilized to provide safe care to all patients with or without COVID-19. Nurses achieved safe care by responding quickly and continuously to the always-changing organizational conditions such as cross-training staff deployed to other clinical departments, adjustment and flexibility in personal work schedules, physical changes to nursing units and care environments, and adoption of personal protective equipment.

Throughout the pandemic, nurses mobilized to provide safe care to all patients with or without COVID-19. Nurses achieved safe care by responding quickly and continuously to the always-changing organizational conditions such as cross-training staff deployed to other clinical departments, adjustment and flexibility in personal work schedules, physical changes to nursing units and care environments, and adoption of personal protective equipment.

Stresses associated with these disruptive conditions were compounded by nurses’ fears of contracting the virus and transmitting it to family and friends Over a short period, the intersection of a high consequence and uncertain contagion with the navigation of new work roles and environments created a perfect storm, disrupted organizations across all levels and systems of patient care delivery and personal self-care, and affected the very fabric of American life. The disruption's magnitude, breadth, and scope for nurses established the foundation for a potentially traumatic situation. As providers who are closest to patients, nurses were most vulnerable to negative effects on their physical and psychological well-being.

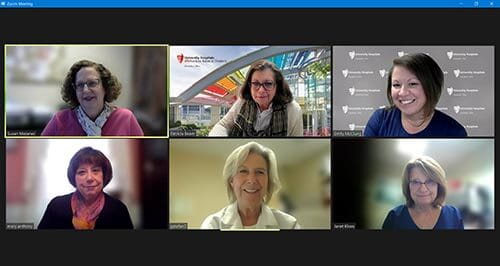

In March 2020, in an escalating situation, several nurse scientists from across UH Cleveland Medical Center began to discuss the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nurses. The team of researchers included Drs. Mary Anthony, Susan Mazanec, Patricia Beam, Jan Kloos, Emily McClung, and Gladys Stefanek, an APP in Seidman. Turning to the literature, the team found initial studies from China reporting nurses as having moderate levels of anxiety and depression, including physical symptoms. In the team’s discussions, they speculated whether or not potential positive effects might also be an outcome of the situation and what factors might determine whether positive effects such as post-stress growth might also occur. As discussions progressed, the UH team of nurse researchers committed to looking beyond and focus on negative responses by including the potential for personal growth during these challenging times. The aims of the study include:

- Describe COVID-19 work-related disruption and sources of nurse exposure;

- Examine nurses’ positive and negative responses to the pandemic; and

- Describe the nature and frequency of the network of personal and organizational supports used by nurses.

The COVID-19 UH Nursing Study was a cross-sectional, descriptive, correlational design conducted across the UH system, including UH Cleveland Medical Center and 14 community hospitals and ambulatory areas. 6,628 RNs and APRNs working in any specialty within acute or ambulatory care and regardless of clinical role or full- or part-time status were invited to participate in the study, and 1,009 completed the survey. Nurses who participated in the study were primarily clinical, direct care providers with over 14 years of experience working full time in inpatient areas during the initial phase of the pandemic from March 17- May 1, 2020.

Our findings demonstrated that responding nurses reported low stress levels. Nurses who provided direct care to patients and reported being exposed to COVID-19 were more likely to have higher levels of stress than nurses not providing direct care or not exposed. Younger nurses with fewer years of experience reported higher levels of stress.

Relatively low anxiety levels were reported, but on closer examination, 38% of nurses reported moderate-to-severe anxiety. Higher anxiety levels were associated with younger nurses and fewer years of experience. Similar to the stress findings, nurses diagnosed with or exposed to COVID-19 reported higher anxiety than those not diagnosed or exposed.

Generally, nurses reported low-to-moderate stress-related growth across the five specific types of growth (relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual changes, and appreciation of life). Nurses diagnosed with COVID-19 also reported more growth than those not having the disease.

Our team explored how stress, anxiety and growth might be impacted by the network of social supports available to nurses, included peers, family, co-workers and managers. Nurses perceived receiving high family and peer support while support from co-workers and managers was more moderate. Of the 17 supports offered by the organization, nurses engaged in an average of 2.5 activities with a usage range of 2-56%.

The role of social support was also examined at a higher statistical level to understand how it influenced the relationship between stress and anxiety with stress-related growth. Family, peer, co-worker, and organizational supports were direct predictors of stress-related growth. Supervisory support was not a direct predictor of post-stress growth, but supervisory support moderated the relationship between stress and stress-related growth under certain conditions. In other words, when supervisory support was low, stress was not associated with post-stress growth. Conversely, higher stress were associated with stress-related growth when supervisory support was high.

While the COVID-19 pandemic remains a healthcare crisis, results from this study may provide direction to effective support used by nurses. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to highlight the role of a network of supports to positive adaptation to the pandemic, particularly the role of the nurse manager as instrumental to nurses’ growth during periods of high stress. Whether individually or globally focused, organizational offerings that support mental well-being positively impact nurses’ stress and anxiety levels.

Patricia Beam, DNP, RN, NPD-BC

Susan R. Mazanec, PhD, RN, FAAN

Janet A. Kloos, RN, PhD, APRN-CCNS, CCRN

Emily L. McClung, PhD, RN

Gladys Stefanek, NP, CNS, CBCN

Mary K. Anthony, PhD, RN